There are four castes in India; the priests, the knights, the traders and the hand workers. Everybody belongs to one of these castes – if they are lucky.

If not, they are dalits, outcastes, who have to do all kinds of dirty work for the rest of the society. Officially the cast system is eliminated, but it still plays a strong role in society.’ That was my imagination of the indian society, promoted by german documentaries and books about the subkontinent – before I arrived here.

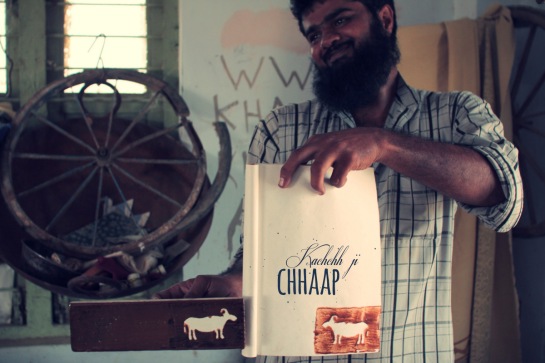

A while ago we interviewed several tie and dye (Bandhani as it is called here) artisans in the Kutch region for an upcoming exhibition. While visiting all these artisans and talking to them, one sentence got embedded deep into my mind.

I am a filmmaker from Germany. I did many interviews in the past, when I was working for a news channel in my country. While I tried to avoid politicians and other representatives of big enterprises who talk a lot without really saying anything, I really enjoyed talking to artisans, who mostly give a flaming speech about what they do, why and what is the bigger philosophical context. They are a gift for every filmmaker.

So when the question: “Why are you doing Bandhani?“ was asked to Abdulbhai, who is a Khatri and a Bandhani artisan, I expected a long monologue about colours, the artistic approach to design something unique, or the meaning of hand-work in general. But then, Abdulbhai’s answer was one simple sentence:

“I am a Khatri, this is what we do.“

For a short moment I looked inward. “What is this? And what should that mean, I am a Khatri, this is what we do? I don´t understand.”

Also our interviewer/ translator looked a little bit confused and tried to request a longer and more emotional answer. But the response we got was rippled eye-brows which emphasized what kind of a stupid question that was. It remained only that simple statement.

I heard that answer again and again and every time it left a big question in my head. How can someone not question what he is doing? Why do people become something only because their fathers and grandfathers did it? It would never occur to me to become a carpenter only because my dad is one. I become a carpenter, because I am convinced this is a useful profession, because I want to work with my hands, because I want to be the best builder of high-quality furniture..There are 1000 reasons why I may want to become a carpenter, but none of them would be;

“I am a Klare, this is what we do”.

It is right, I did not understand. Why? Because I did not understand the basic concept of a community. To understand the concept of communities, I first have to explain another misunderstanding. The four step caste pyramid I mentioned in the beginning does not exist in that black and white form. In the larger picture, everybody is part of a certain community. A community describes one group of people who have the same last name (without necessarily being related to each other). Besides the same name they share their own traditions, their own livelihood, clothing style, cuisine, rules for marriages… The Khatris for example are a community of textile printers and dyers. In Kachchh, they are largely Muslim. There are Hindu Khatris as well.

Like ‘the Khatris’, there are several hundreds of small communities all over India, and the affiliation is especially high in little villages.

I am not really sure how and when the community system evolved. Probably it was some thousand years ago, when people from all over asia came to India. Every group of people had their own livelihood, their profession and according to that, they would identify themselves as one community. They learn the skill from watching their fathers and grandfathers at work. They take over when they are older. It is what they know. It is what they are known for. It is such a big part of people´s identities, that they give themselves to a profession and a certain way of living, because this is what their community is doing.

For someone who is educated to think independently, this is indeed hard to understand.

Not to create a glorified picture, Kutchi people don´t live behind the moon in their little cottages without any contact to the outside world. Many people even in the villages have a smartphone, some a computer, some decide to leave the village and learn something else. But despite all this, the tradition and the “belonging” to a certain community still makes a big part of one’s identity.

“I am a Khatri. This is what we do.”

I am always struggling, trying to find out what I should do and always question why and if there is not something better, more interesting, exciting, meaningful?

Too many choices, too much confusion. Meanwhile, AbdulBhai is not asking.

He knows what to do, he is a Khatri, a dyer.