On my first drive into the Banni grasslands back in February, I had a hard time believing what the ecologist next to me was saying. At the time, we were on an empty highway heading due north. On either side of us the land was flat, brown and stretched out endlessly, scattered with a few tufts of dry grass and a lot of a small, hardy looking thorny tree species. I wondered idly why people called it a grassland. There wasn’t all that much grass in sight.

“It looks brown now,” he said, “but wait till it rains! The grass comes up and all the land you’re looking at turns into a marsh. It’s just water and grass, as far as you can see.” Another co-worker said, “Just wait till it rains, Banni turns into a golf course!”

I was skeptical. Even more so a few months on, when the summer heat hit Kachchh in earnest and Banni turned into a giant duster with towers of it scudding across the landscape. After every visit I went home with an unavoidable fine layer of grit embedded on my skin and in my teeth. Wait till it rains, they said. Word on the street was Kachchh might have another year of drought.

Banni is the subcontinent’s largest natural grassland, but it doesn’t always look that way. People who knew the area thirty or more years ago reminisce fondly about the height to which the grass would grow, the way it would be hard to spot a buffalo walking through it. It’s a difficult vision to conjure for those of us encountering Banni for the first time today. The spread of Prosopis juliflora, or Gando Baavar (Crazy Weed) as it is locally known, has been devastating. Fiercely invasive, Gando Baavar is everywhere. While there is grass, quite a bit of it, in the dry months a first time visitor would be forgiven for thinking they’d ventured into a particularly barren stretch of thorny forest rather than a grassland.

For 500 years or more, this region has been home to pastoralist communities, the Maldharis, who keep buffaloes and cows and graze their herds across the expanse of the land. What happens to your livelihood when your grazing dries up? Resourcefulness is a quality found in abundance here, from the structure of virdas, local water harvesting systems, to the buffaloes themselves, who are well adapted to their harsh environment and invariably find something to chew on.

Regardless, whenever there is good rain in some part of Banni, word spreads quickly and people move out with their herds. The communities living in the region of good rain never begrudge the presence of these travellers, and grazing is shared equitably. In Banni there is never any doubt that community welfare trumps the individual rat race, and the welfare of the animals is the ultimate priority. Wherever you go, you are welcomed, you are fed, you are family.

In September it rained for a week. There was lightning and thunder, downpours and flooded homes. In Bhuj, the lake overflowed prompting two days of public holidays. In the eastern belt of Banni though, where 300 families had migrated to avail of the grazing provided by earlier, sparser rains, things were difficult. A Maldhari friend who was there told me later that the water had been as high as his chest. Over 100 buffaloes drowned. “It’s not so hard for the maldhari with 30 or 40 buffaloes,” he reflected as we talked about the flood, “but what about the man who lost his only milk producers?”

That man, and others like him, will pull through. Their community will see to it that they do. Rain brings immense optimism to this water bereft land, and it is infectious. It’s hard not to look at the bright side. I find that my skepticism has dissolved and Banni is indeed a golf course.

On the way to a meeting in Banni the other day, we came upon a few Maldharis leading their buffaloes home from the eastern belt. We hopped out of the car to walk a while with them, till our paths diverged and we went on to our meeting while they turned toward their village. Despite recent events, the mood was calm, untroubled. In Banni, they had always known that the rain would turn up this year. But how?

“The buffaloes had the right body language,” one Maldhari said. “If the rain wasn’t going to come, they would have known.”

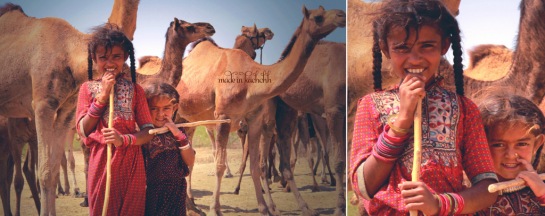

Although their mother had not come along at that time, I later found out that she plays a key role in their lifestyle. She builds their home, she takes care of young camels when they are born and collects grasses to feed them. She prepares food for the family, typically consisting of camel milk, rotlo (wheat or millet bread) and tea.

Although their mother had not come along at that time, I later found out that she plays a key role in their lifestyle. She builds their home, she takes care of young camels when they are born and collects grasses to feed them. She prepares food for the family, typically consisting of camel milk, rotlo (wheat or millet bread) and tea.

These two girls had accompanied their camel-breeder daddy to work yesterday. It seems they come everyday, with their herd of 30-40 camels to graze them in the thorn forests.

These two girls had accompanied their camel-breeder daddy to work yesterday. It seems they come everyday, with their herd of 30-40 camels to graze them in the thorn forests.