“Breath in,” Dr. lsmail Khatri pushed a yellow scarf in front of my nose in Ajrakhpur, a village of families dedicated to block-printing in Kutch, a semi-arid region of Northwest India.

It smelled like my lunch.

“Turmeric and Pomegranate skins for yellow,” Dr. Ismail explained. The smell is the way buyers ensure that the dye used is not synthetic.

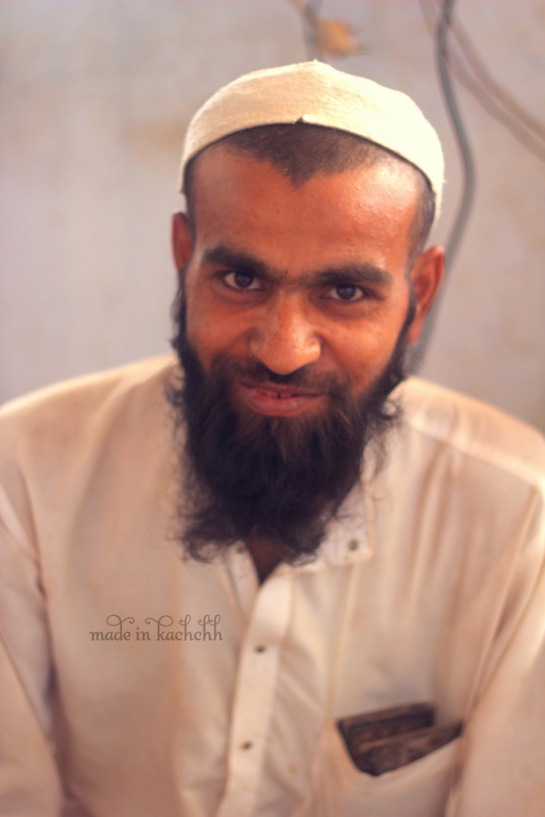

Dr. Ismail was born into a centuries-old tradition of Ajrakh, or block-printing. His ancestors were recruited to Kutch from a historic province of Pakistan, Sindh, at the king’s request for handmade textiles in the 16th century. Now, he and his sons Sufiyan and Juned run a natural-dye Ajrakh operation. Their family home is a sanctuary for seekers of handmade textiles in India.

Under the ceiling fan in Dr. Ismail’s office, I unfold and refold hundreds of meters of handprinted fabric, layering myself in enough colors to rival Joseph. I ask about the patterns draped over my shoulders and learn that the teardrop shapes aligned in dizzying symmetry signify khareks, or sweet dates. Following the Muslim tradition, Ajrakh designs are aniconic: they do not depict human or animal figures. Instead, they represent local botany, ceremonious fruits and interpretations of the night sky.

I unearth the deepest colored fabrics from the Khatri’s inventory and hold them against my face in front of a mirror. In some communities of Kutch, color intensity of Ajrakh textiles denotes age: younger women wear lighter shades and graduate to darker colors with age, depicting the depth of their wisdom. Traditionally, printed motifs in women’s dress shift with each life-cycle.

Women throughout Kutch don unique Ajrakh traditions as communal and individual identification codes. In the Khatri family, when women become married they wear haidharo prints, floral motifs in red and white on a yellow background. When their son marries, their dress shifts to the jimardi print whose floral depictions are more intricate and printed in dark blues and reds on an emerald background. Once widowed, women of the Khatri family adopt the ghaggro print, a floral motif

printed in dark reds and blues. Men traditionally wear red and indigo Ajrakh turbans and shoulder cloths that double as spice sacks or namaaz prayer mats.

I recognize the weight of distinctions that my choice of fabrics carry, but am overwhelmed by my mission to select the prettiest. I leave them folded on a chair when Sufiyan’s wife, Hamida, calls me into the kitchen. I watch her peel carrots and hold her toddler until he starts crying. She takes her child and hands me a carrot peeler. Together we cook Gajar Halwa, a sweet made from carrots, sugar and cream straight from the family’s buffalo herd. Gajar Halwa is a treat traditionally prepared for special guests, of which the Khatris have no shortage. Designers, students and textile enthusiasts stream into their home to touch, smell and purchase Ajrakh textiles.

…

Nine hundred and fifty kilometers south of Kutch, Dr. Ismail’s cousins, Ahmed Khatri and his son Sarfraz run Pracheen, a block-printing studio in Mumbai with a kindred buzz. Years ago, Ahmed learned natural dye recipes and techniques from Dr. Ismail, into which he has since infused mysterious secret recipes that seduce some of the world’s top designers and India’s most worshiped Bollywood heroes.

From the outside, the Pracheen workspace in Southeast Mumbai is unremarkable. The main door is hidden amongst hundreds of others that look just like it surrounded by mobs of peddlers, merchants and animals. Inside, three dark flights of stairs with no railing lead to a small office that opens into a grand studio of long tables set with meters of stretched handwoven silk or organic cotton. Barefooted men shuffle along the narrow tables as they thump wooden blocks onto white space in a steady beat.

I remove my shoes and let myself into the studio. I pause in reverence as I witness the thousands of hand-carved wooden blocks stacked on top of one another and organized by the motifs carved into them. They line the walls of the studio representing hours of labor at the hands of artisans. Ahmed’s family lives on the floor below the studio and his goats occupy the rooftop terrace. Ahmed and Sarfraz serve fresh coconut water to each visitor, a trademark of their customer service.

“Do you know a woman from America . . . her name is Donna Karan?” Sarfraz asked me as I sipped from a fresh coconut.

“Like . . . The DKNY?” I asked. “Last week she spent eight hours looking at our cloth.” He handed me a photograph of Donna Karan swaddled in Pracheen shawls.

The Khatri operations in Ajrakhpur and Mumbai are both thriving. The families share a deep reverence for Mohammed, vowing that faith fuels their commitment to craftsmanship and beauty. While sharp contemporary angles mask some traditional motifs on the printed fabric, underlying patterns can be recognized in Islamic art and architecture. The Khatris credit God for their inspiration, creativity and business acumen.

The name Khatri translates literally into one who fills with color. The cousins in Ajrakhpur and Mumbai have the same indigo-stained nail-beds, exposing their possession of the secrets that transform local nature into vivid textiles. Both families honor the environment through preservation of water and commitment to the use of natural colors such as indigo, madder and turmeric instead of synthetic dyes.

Dr. lsmail remembers rubbing pomegranate skin water onto fabric as a child. His family was one of the first in India to document experimentation with locally found materials as textile dyes. When I first visited him, he took me on a tour of his backyard and led me to a tree.

“The bark is used for orange color,” he said, plucking at its trunk.

He then led me to a bucket of murky stew made from “rusty things” (bicycle pieces and scraps of fences). It had been fermenting with sugar cane and chickpea flour to yield a black color, which is used to outline the intricate designs on Ajrakh fabric. I gagged when I leaned over the top to look inside.

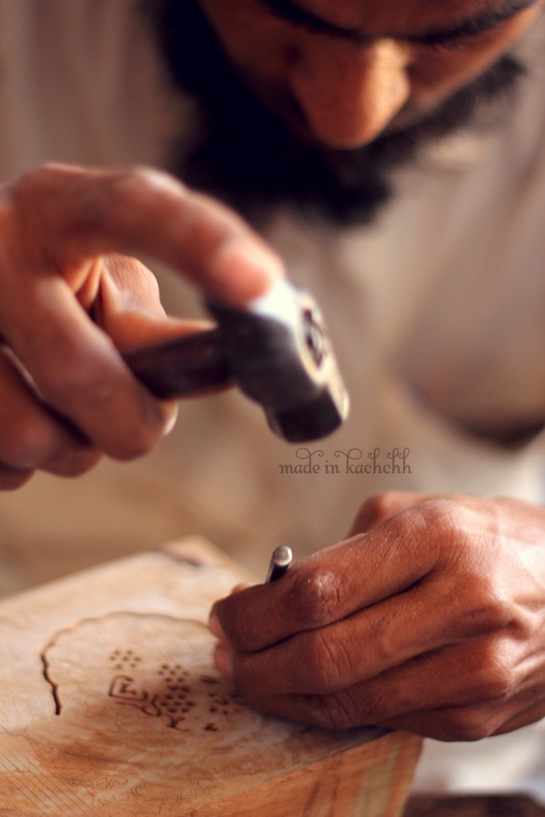

The art of Ajrakh seems to be magic, but the process is precise and laborious. White cloth is stretched and pinned onto a table. Printers, men trained in the precise art of Ajrakh, dunk wooden blocks into pastes of mud, resists that shield the adherence of dye to fabric and mordants that react with natural chemicals to absorb certain dye colors. The pastes are made from common ingredients including tamarind seed, arabic gum, clay and millet flour.

The printers, men from nearby villages, hover the mud-painted blocks over cloth to ensure symmetrical application and pound them with heavy-forced whacks hundreds of times until the cloth is completely stamped with designs. Sawdust or buffalo dung is immediately sprinkled on the fabric to prevent the prints from smudging. It is sunbathed to dry and then dipped into fermented indigo, which is light green until it is oxidized into deep blue. After it dries in the sun again, it is washed and beaten, removing the mud pastes from the cloth. This process is performed several times until the cloth is transformed into a multicolored mural crowded with time-honored motifs.

Historically, Ajrakh was an important part of the economic web that sustained Kutch’s interdependent barter relationships among families. A family of weavers might trade hand-woven turbans and shawls to the Khatris for printing. The Khatri wives might embroider ornamentation onto the pieces before trading them back to the weavers for more goods. High-skilled artisans reserved their masterpieces for dowry collections and labored over unique ornamentations for wedding celebrations. Families created handcraft in synchronicity with community needs.

Today, the Khatris’ work is celebrated on international runways. Dr. lsmail, Sufiyan, Juned, Sarfraz and Ahmed work closely with designers from all over the world and study fashion magazines to broaden and enhance their tradition. Visiting designers can draft their own wooden blocks, but most choose from the Khatris’ traditional collections. Blocks are retired when the edges turn rough or become uneven. Dr. lsmail has blocks that are over 200 years old.

…

When I step into the Khatri sanctums, my heart beats faster. I touch everything from the frayed edges of unfinished samples to the cheeks of children playing with wooden blocks. I hold babies, pour chai and wander into kitchens. I feel cloth for rough edges, loose loops of thread and spots where the dyes didn’t soak in evenly.

When I was young, my mom was my personal shopper. She’d come home with multiple outfits and force them over my head as I stood passively with my arms up. She usually ended up returning all of her purchases, only to try again. I hated shopping. I still can’t figure out how to select the right blouse out the hundreds of starched variations, each with crunchy paper tags dangling at their sides. The gaudy colors and crisp fabrics that hang perfectly under the fluorescent overheads are supposed to go on my body? The idea of it feels too far away.

Shopping for Ajrakh is a loaded venture. My purchases are guided by human connections and histories that come alive in the fabric. I shell out too many rupees without regret because I know that the shawls I purchase are stamped with pride, tradition and God’s mysterious company.

————————————————————————————————-

This article contributed by a dear friend Shaina Shealy, originally appeared in the Hand Eye magazine more than a year ago. Shaina is a wonderful photographer and story-teller who loves (and lives) to cook and feed people! Here is a link to her mom and daughter food blog, handcrafted with love, Cross Counter Exchange

Thank you Shaina! And much love from Kachchh!

————————————————————————————————-

Visit Kachchh Ji Chhaap, an exhibition of 500 years of Batik and Blockprint at Khamir, Kachchh

![Final Invite CC [Converted]](https://madeinkachchh.files.wordpress.com/2015/01/1-invite_ghadai.jpg?w=545&h=365)