Khalid’s advice to us, “Go home. Enough of film shooting. It is not good to go crazy about your work. It can be disastrous!”

The film team!

Watch the movie on youtube,

Even after all these years, Musabhai remembers precisely the printed motif that he sold to a businessman in Ahmedabad when he was just a teenager traveling out of Kachchh for the first time. He showed me the fabric sample and said, “I had made so many blocks myself and stored them all in my work shed in Dhamadka. Then the earthquake came, and the ground shook and the blocks were completely smashed! Not one survived. So I moved to Ajrakhpur and remade them all again!”

Musabhai today is a successful businessman. With his two sons helping him in printing and dyeing, theirs is one of the most visited shop in Ajrakhpur. What we went to document in film was his ‘businessman skills’ and what we received in return was a whole lot more.

“Is she understanding everything I am saying?” he asks pointing towards Sarah who is filming us.

“No Musabhai, I don’t think so. After going home, we both will sit together and translate every word that you said and then she will understand.”

“But my words are ok?”

“Your words are perfect!”

Later on, inside a workshop a few meters ahead, Khalid makes a beautiful hand printed and painted masterpiece, all the while making jokes about why we came to live in Kachchh and work at Khamir and what is our salary! Khalid is one of a kind artist…and person. Truly. Try talking to him and you will see how!

🙂

This short glimpse into the lives of Khatris of Ajrakhpur could well have been made into 5 films if not for Sarah’s super editing skills. So many laughs, discussions, debates, bad sound recordings and mutton meals later, we ended up with this. Those were indeed some special moments and I am glad Sarah could put it all together so nicely, in this film “A New Beginning In Ajrakhpur”.

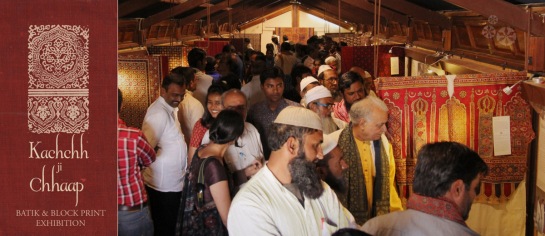

Bringing together the Block printers and dyers of Kachchh and Khamir, our exhibition ‘Kachchh Ji Chhaap’ is now open!

The exhibition is an attempt to tell the story of prints and print making as it unfolded from the time it was practiced on the banks of the Indus to its many facets today. Kachchh Ji Chhaap is an intricate tale of the craftsmen, bringing together narratives of their lives, their milestones and their challenges.

The Exhibition will be held at the Khamir Campus from 7th December 2013 to 28th February 2014.

There are four castes in India; the priests, the knights, the traders and the hand workers. Everybody belongs to one of these castes – if they are lucky.

If not, they are dalits, outcastes, who have to do all kinds of dirty work for the rest of the society. Officially the cast system is eliminated, but it still plays a strong role in society.’ That was my imagination of the indian society, promoted by german documentaries and books about the subkontinent – before I arrived here.

A while ago we interviewed several tie and dye (Bandhani as it is called here) artisans in the Kutch region for an upcoming exhibition. While visiting all these artisans and talking to them, one sentence got embedded deep into my mind.

I am a filmmaker from Germany. I did many interviews in the past, when I was working for a news channel in my country. While I tried to avoid politicians and other representatives of big enterprises who talk a lot without really saying anything, I really enjoyed talking to artisans, who mostly give a flaming speech about what they do, why and what is the bigger philosophical context. They are a gift for every filmmaker.

So when the question: “Why are you doing Bandhani?“ was asked to Abdulbhai, who is a Khatri and a Bandhani artisan, I expected a long monologue about colours, the artistic approach to design something unique, or the meaning of hand-work in general. But then, Abdulbhai’s answer was one simple sentence:

“I am a Khatri, this is what we do.“

For a short moment I looked inward. “What is this? And what should that mean, I am a Khatri, this is what we do? I don´t understand.”

Also our interviewer/ translator looked a little bit confused and tried to request a longer and more emotional answer. But the response we got was rippled eye-brows which emphasized what kind of a stupid question that was. It remained only that simple statement.

I heard that answer again and again and every time it left a big question in my head. How can someone not question what he is doing? Why do people become something only because their fathers and grandfathers did it? It would never occur to me to become a carpenter only because my dad is one. I become a carpenter, because I am convinced this is a useful profession, because I want to work with my hands, because I want to be the best builder of high-quality furniture..There are 1000 reasons why I may want to become a carpenter, but none of them would be;

“I am a Klare, this is what we do”.

It is right, I did not understand. Why? Because I did not understand the basic concept of a community. To understand the concept of communities, I first have to explain another misunderstanding. The four step caste pyramid I mentioned in the beginning does not exist in that black and white form. In the larger picture, everybody is part of a certain community. A community describes one group of people who have the same last name (without necessarily being related to each other). Besides the same name they share their own traditions, their own livelihood, clothing style, cuisine, rules for marriages… The Khatris for example are a community of textile printers and dyers. In Kachchh, they are largely Muslim. There are Hindu Khatris as well.

Like ‘the Khatris’, there are several hundreds of small communities all over India, and the affiliation is especially high in little villages.

I am not really sure how and when the community system evolved. Probably it was some thousand years ago, when people from all over asia came to India. Every group of people had their own livelihood, their profession and according to that, they would identify themselves as one community. They learn the skill from watching their fathers and grandfathers at work. They take over when they are older. It is what they know. It is what they are known for. It is such a big part of people´s identities, that they give themselves to a profession and a certain way of living, because this is what their community is doing.

For someone who is educated to think independently, this is indeed hard to understand.

Not to create a glorified picture, Kutchi people don´t live behind the moon in their little cottages without any contact to the outside world. Many people even in the villages have a smartphone, some a computer, some decide to leave the village and learn something else. But despite all this, the tradition and the “belonging” to a certain community still makes a big part of one’s identity.

“I am a Khatri. This is what we do.”

I am always struggling, trying to find out what I should do and always question why and if there is not something better, more interesting, exciting, meaningful?

Too many choices, too much confusion. Meanwhile, AbdulBhai is not asking.

He knows what to do, he is a Khatri, a dyer.

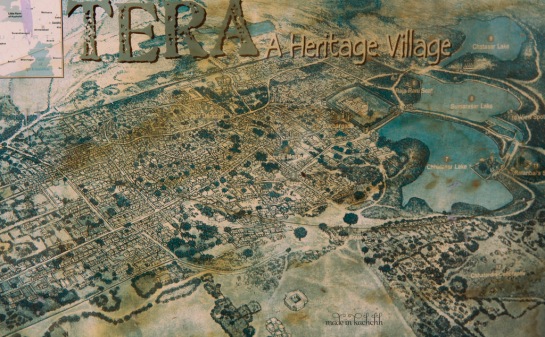

Nearly four centuries ago, a tiny village nestled in the Naliya grassland region of Kutch was sold for tera hazaar (thirteen thousand) koris (an ancient currency of Kachchh). It was an important port during that time and along with the other ports like Mandvi and Mundra, it contributed to much of the maritime trade between India and the Middle East, Africa and even the West. It was home to rich Hindu, Jain and Muslim merchants, who patronized the construction of beautiful havelis and marketplaces, temples and stepwells, tombs and mosques that adorn the streets.

This little village came to be known as Tera which means thirteen in Hindi.

Today, a walk through Tera reminds you of a once flourishing medieval town, retaining much of its symbolic power and grandeur in its architecture. The streets are straight and narrow, with an imposing fort wall dressed in stone known as the ‘Alampanah’.

If you happen to catch the chatting villagers during their afternoon tea time, they will proudly tell you what is perhaps the most unique feature of their village. The manmade lakes. To the North-East of the village, along its periphery lies this fascinating example of traditional water management systems. They are called the Chhatasar, Sumarasar and Chatasar.

Rainwater collected from the hills about 15-20kms away is brought to the village through a small canal. It flows first into the Chhatasar whose banks are sealed against erosion and the bed against percolation. The water from this lake gets filtered through a wier on the opposite end and flows into the second lake, the Sumarasar. When this gets filled up, it automatically flows into the third, Chatasar and eventually into the river Tera. This interlinking and sequential filtering of rain-water is remarkable.

The use of the three lakes was segregated into bathing and washing clothes, for animals, for drinking and other needs respectively.

Imagine the engineering skills of these people back then!

Aziz and Suleman Khatri are a terrific team. They are artists and brothers in the business of Bandhani, a craft that has remained in their family for nearly seven generations.

They live in a town called Badli in the district Nakatrana of Kutch.

“We need to give bandhani a modern look. People already own the old bandhani designs, they are sitting in their cupboards, so we need to do something different.” says Suleman.

“We need to give bandhani a modern look. People already own the old bandhani designs, they are sitting in their cupboards, so we need to do something different.” says Suleman.

The brothers have a zest for experimentation. Both graduates from the artisan design school in Kutch called Kalaraksha Vidyalaya, they have together set new standards in design and expression of this traditional art.

The family has also developed new ideas and color schemes for their products by working with designers from other Indian cities. While Aziz is the brain between the development of new concepts, designs and colours, Suleman handles product development and marketing.

The family has also developed new ideas and color schemes for their products by working with designers from other Indian cities. While Aziz is the brain between the development of new concepts, designs and colours, Suleman handles product development and marketing.

“Artisans need help understanding their consumers, markets, colors, designs, and materials that sell,” says Aziz, “That is what the government and the NGOs can do. Many artisans do not know what sells and are not aware of market trends, so once they have this understanding, they can advance their craft.”

“Artisans need help understanding their consumers, markets, colors, designs, and materials that sell,” says Aziz, “That is what the government and the NGOs can do. Many artisans do not know what sells and are not aware of market trends, so once they have this understanding, they can advance their craft.”

——————————————————————————————————

——————————————————————————————————

From September 2012 to February 2013, a team of us have been travelling around Kachchh searching for stories of Bandhani artisans. We spoke to a small handful in each region to get a glimpse into their lives and histories. We found stories of hope, risk, creativity, determination and passion.

Voices of the community is a collection of all these creative people across Kachchh and what they have to say. Visit Bandhani : Ties, Dyes and Bumpy Rides for more.