It is the sunny season in Kachchh and the air is dry as ever. In the middle of the dryland somewhere in Western Kachchh, there lies a big pond where camels, we are told, stop for their mid-day drink. It is here that we wait for Ahmed-bhai to arrive with his herd of camels, and to my amusement, his two little girls!

Ahmed-bhai is a “maldhari”, a herder who breeds and looks after camels. A nomadic lifestyle keeps him and his family constantly on the move both within and outside of Kachchh. His family belongs to the Jat community whose forefathers are believed to have fled from Haleb in Baluchistan about 500 years ago. Following a feud with the King, the Jats sold all their other animals and replaced them with camels to prepare for their long journey traversing Sindh to eventually settle in Kachchh.

Mainland Kachchh has always lacked fertile soil. Just down south of the Great Rann of Kachchh, lies however Asia’s largest grasslands called the Banni. This led to a dependence on pastoralism, with camel breeders, sheep and goat herders, cow and buffalo breeders inhabiting the region for over five centuries.

A little while later, the camels arrive and move slowly towards the water edge. Within a couple of minutes we are surrounded by 40 thirsty camels. As if by ritual, the camels are milked and fresh camel milk is offered to us. “Start with a little if it is your first time.” they say to me. I slowly take a sip, I have never tasted such salty milk before! They call me to the pond and offer clear water collected from inbetween a few rocks, “Drink! Aren’t you thirsty?”

I take a large sip again.

To be a nomadic pastoralist is to lead a life of discipline guided by the principles of nature and animals. Pastoralists have always lived in complete harmony with their surroundings. They had formed unique bonds with the other communities from the region. Eiluned Edwards in her article about the symbiotic relation between pastoralists and other communities writes that farmers in Kachchh would welcome migrating herders and their animals into their farm land after a monsoon harvest had been made. The animals would graze on the stubble, effectively clearing the land for the next season’s sowing while their urine and manure replenished the land, acting as a natural fertilizer. In return the nomads would be given grains for their service. In addition, the farmers would get milk and ghee (clarified butter) from the nomads.

The nomads had a similar relationship with the Khatris (one who works with colour on textiles) in the region. The khatris made colourful clothes for the nomads, and were paid in milk and ghee. Sometimes, the extensive knowledge of the khatris of local herbs and plants came useful in the case of an animal from the herd that needed medical attention.

During the Green revolution, a lot of this changed. Extensive agricultural practices introduced year-round cultivation, fertilizers and eventual loss of grazing land. These changes tragically affected the nomadic pastoralists.

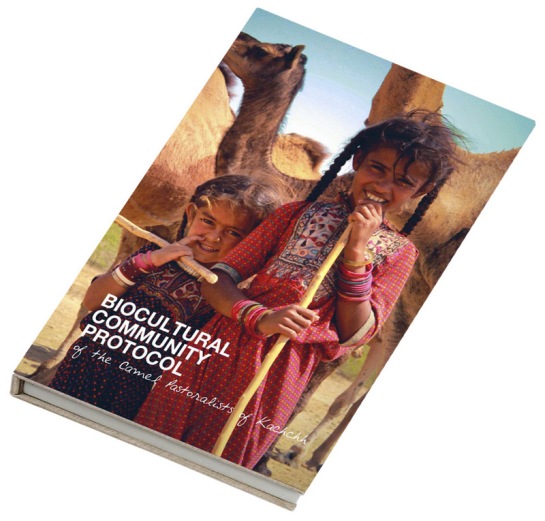

This afternoon however, unaware of the struggles with their semi-nomadic lifestyle, I sit watching in admiration. The young daughters Noorbhanu (5) and Hanifa (10) now have a fan. Hanifa displays such confidence with the animals, running behind the stray ones to bring them back to the pack. Her little sister Noorbhanu is always 2 steps behind her, strong and quick in their movements, I can see that they have already mastered their father’s work. When our eyes meet, I see the shyness and the curiosity of little girls.

“Do they come everyday?” I ask their father. “Oh yes! They love their camels!” he says.

Although their mother had not come along at that time, I later found out that she plays a key role in their lifestyle. She builds their home, she takes care of young camels when they are born and collects grasses to feed them. She prepares food for the family, typically consisting of camel milk, rotlo (wheat or millet bread) and tea.

Although their mother had not come along at that time, I later found out that she plays a key role in their lifestyle. She builds their home, she takes care of young camels when they are born and collects grasses to feed them. She prepares food for the family, typically consisting of camel milk, rotlo (wheat or millet bread) and tea.

Constant travel means their houses should be easy to construct with few and inexpensive building materials. Their special houses, put up entirely by the women in the family is known as the Pakka, made of kal (reed grass), jute ropes and wood. Between house work, the women also embroider clothes, quilts and if unmarried, their wedding clothes.

The camels have fed and drunk. They have been milked. They will now be sheared for their wool. Soon all the attention shifts to two maldharis, friends of Ahmed-bhai, who with their scissors select a camel with a good tuff of hair on him and begin to shear.

Ahmedbhai collects the hair and puts them in the make-shift cloth bag. Noorbhanu carefully picks up a tiny handful of camel hair from the ground that her father had forgotten. She hands it over to him. “She is very careful, my daughter!” he laughs.

Traditionally camel wool is used to make cheko; bags that are used to cover the udders of the female camels to prevent the young ones from suckling. Today they are giving the wool to Sahjeevan, who in association with Khamir are finding new markets for camel wool to increase income and encourage camel breeders.

Camels are sheared once a year. just before the onset of summer. This work is done entirely by hand. Some maldharis often shear their camels in wonderful patterns, as a result decorating their animals. It is possible to collect 1kg of wool from each animal every year.

Once the shearing is done, Hanifa, the older daughter goes away alone with the entire herd, taking the sole responsibility to direct them to their home. Meanwhile Ahmed-bhai sits down with the team from Sahjeevan to discuss matters. We find a small narrow path inbetween a few bushes where the ground is shaded and cool. We have all run out of drinking water, but no fear, the pond is closeby.

We talk for nearly an hour before Noorbhanu starts getting impatient. She nudges at her father and whispers in his ear. Her father smiles and continues talking. Two minutes later she says, “Enough of chatting papa. How much talking can one do! Let us get to work!”

She is applauded by all of us. Wah Wah.

———————————————————————————————————————

The visit to the pond this afternoon was a part of meeting and understanding the lives of the nomadic herders, for the project – The Biocultural Protocol Of Camel Breeders Of Kachchh.

Their life and spirit is fearless, this is how they have always been.

Here are more photos from this day,

———————————————————————————————————————

I could not meet Noorbhanu’s mother, however here is an album of the women from the Jat Community, thanks to Sahjeevan.