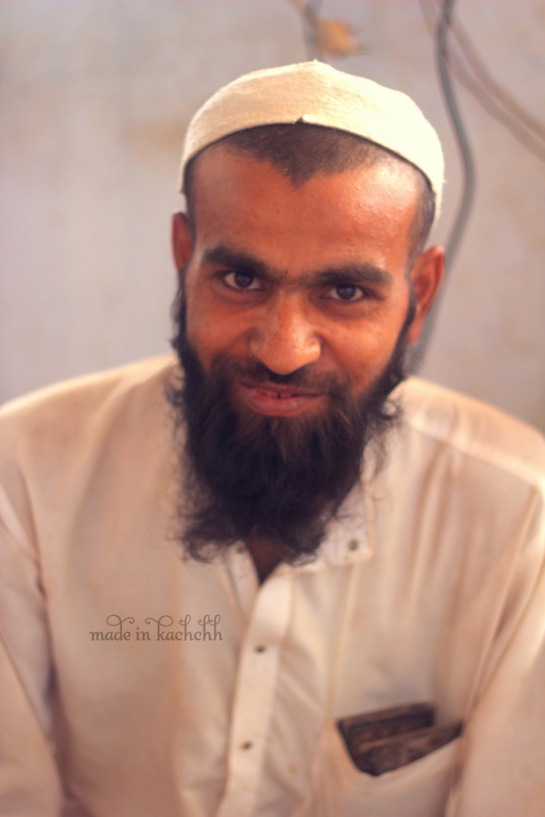

When we arrived in Ajrakhpur, Hojefa was not home … so we sat in front of his workshop. After the earthquake in 2001, a large number of workshops were built in the village to encourage the artisans to keep their craft of ‘Block Printing’, alive. They all look a bit similar : a concrete structure, flat roofs, a small sitting space in front of the entrance door and a patchwork of randomly spread colours on either side of the entrance wall, memories left by the buckets of dyes which were carried hurriedly in and out the building. But Hojefa’s entrance is different… no colours… but a layer of sawdust spread out on the ground as if an ocean of wood shaving was waiting inside for somebody to open and flow towards us. Hojefa is not a blockprinter, he is the one that makes the blocks for them! And he is the only one in Kachchh. His brother, working next door, explains that Hojefa has gone to Bhuj and will be back soon. He opens the door for us, inviting us to come and sit inside. We are not welcomed by a growling wave of sawdust as I expected but by a sea of saws, wood pieces, cutters, plyers, drills, punch, lime, hammer and a multitude of unknown objects scattered all around the place.The first thought that comes to my mind is “How can u work in this chaos!” And then Hojefa arrives. He quickly cleans a small low table to make me sit. He himself sits on the floor, fitting his whole body in a square foot of cleared space. His smile makes you forget everything that is around…he is an emperor and this is his kingdom. Let’s begin!?

He gathers all the tools that he needs in a few seconds and spreads them on a small foot stool that he uses as a workbench. He explains that this stool was made by his dad, it has 2 small compartments to keep the smallest wood cutters and punch. He then takes position behind his pillar drill and starts showing us how to shape a block.

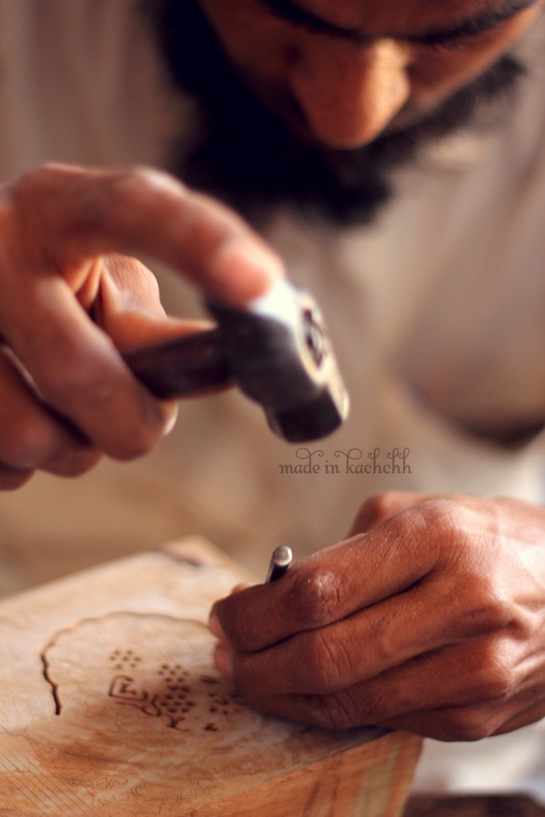

He gathers all the tools that he needs in a few seconds and spreads them on a small foot stool that he uses as a workbench. He explains that this stool was made by his dad, it has 2 small compartments to keep the smallest wood cutters and punch. He then takes position behind his pillar drill and starts showing us how to shape a block.  We are all fascinated by the speed at which he moves the block to carve the shape of the design he has previously marked on the piece of wood. When they were not using a power drill, they used to spend up to 6 days to finish one block. Now, depending on the complexity of the design, it can take a few hours to a day.

We are all fascinated by the speed at which he moves the block to carve the shape of the design he has previously marked on the piece of wood. When they were not using a power drill, they used to spend up to 6 days to finish one block. Now, depending on the complexity of the design, it can take a few hours to a day.

He still wants to show us how a block is made completely by hand and makes us go through the whole process. Marking. Shaping. Drilling. Cutting. Carving and Cleaning.

He still wants to show us how a block is made completely by hand and makes us go through the whole process. Marking. Shaping. Drilling. Cutting. Carving and Cleaning.

The intricacy of the design is impressive and his precision and patience to transform it into a block is mind blowing. The shape that he is making will then be used to print thousands of meters of cloth, a single mistake will also be visible that many times… He is one more essential link in this fascinating chain of human skills that is block-printing.

The intricacy of the design is impressive and his precision and patience to transform it into a block is mind blowing. The shape that he is making will then be used to print thousands of meters of cloth, a single mistake will also be visible that many times… He is one more essential link in this fascinating chain of human skills that is block-printing.

As I pick up a paper with a beautiful ajrakh pattern handdrawn on it, covered with sawdust, swimming in this workshop, I ask him, “Hosafabhai, why aren’t there more block makers like you in Kachchh?”

As I pick up a paper with a beautiful ajrakh pattern handdrawn on it, covered with sawdust, swimming in this workshop, I ask him, “Hosafabhai, why aren’t there more block makers like you in Kachchh?”  He hands me a saucer of chai and says, ” Because you have to sit. You have to sit the whole day. Sit sit sit. Be patient. and concentrate. Sit. It is true that many people know how to make blocks. They have the skill. But they do not want to sit. You have to be passionate and you just have to sit.”

He hands me a saucer of chai and says, ” Because you have to sit. You have to sit the whole day. Sit sit sit. Be patient. and concentrate. Sit. It is true that many people know how to make blocks. They have the skill. But they do not want to sit. You have to be passionate and you just have to sit.”  He spends nearly 2 hours sitting with us, replying to our questions and showing us all the steps of his work. During this entire time I didn’t once think of the chaos that was surrounding us, I only saw his passion, his dexterity, his smile and the beautiful perfection of his work.

He spends nearly 2 hours sitting with us, replying to our questions and showing us all the steps of his work. During this entire time I didn’t once think of the chaos that was surrounding us, I only saw his passion, his dexterity, his smile and the beautiful perfection of his work.

Recipes for Food. Recipes for Life.

We are making movies for the exhibition.

Portraits of towns and portraits of it’s people. The idea evolves everyday. Because life writes way better stories than we could ever think about.

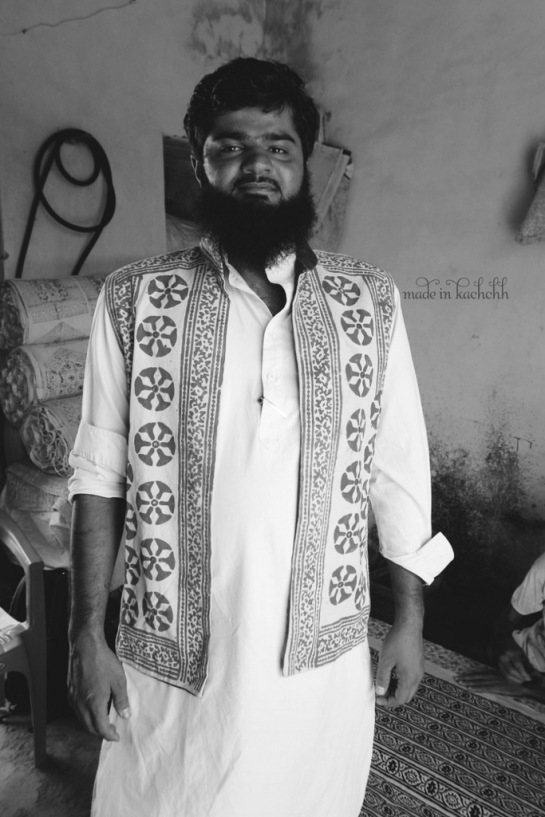

Two days ago we started shooting for our film with Musabhai.

Early in the morning we met him in his shop and planned to spend the day with him. Our agenda – dive into the world of Musabhai the Blockprinter, the Businessman. Follow him in his world of numbers, parcels, and customers. Be big-eared for discussions with clients and tea, the camera always ready to capture what we were hoping for.

Soon it was noon. Sarah and I were discussing scenes and conversations to shoot. Just then Musabhai called out to us, “Come, you can film me cooking.”

We looked at each other, confused.

Just in the morning he had told us that he was not printing or dyeing cloth anymore for some years now. Anyway.

“Maybe he is going to cook some natural dyes in a pot, to colour his cloth, so let’s go!”

While we were still looking at each other in confusion, Musabhai had vanished.

We stepped into the courtyard of his house, but there was no one.

After a few seconds came a voice from inside the kitchen, “Come, come. Come inside. I am cooking!”

Both of us were now grinning from ear to ear.

The businessmen behind the burner? A picture we really didn’t expect.

We will let you watch, Masterchef-Musabhai !!!

—————————–

Together with Khamir and the blockprinters of Kachchh: Kachchh ji Chhaap, 500 years of blockprint. An exhibit coming up soon on 7th December 2013.

The Last Blockprinter of Bela

We are driving through Kachchh, speeding away towards the east.

Today we are going to Bela, a village en route to Dholavira, the historic site of the Indus Valley Civilization. We are in the district of Rapar and I can already see the Rann.

“Shruthi, do you know about the people that live here?”

“Hmm?”

“They do not think twice about picking a fight, and even less before picking up a weapon!”

“Yes, yes, he is right. They are a very fighter type, you should be careful!”

I am warned about rubbing against people on the streets when we get off the car.

I don’t know what to say.

“Arey, it is a joke yaar. Relax!”

Ah.

The other two in the car are nearly snoring.

We started at 6am, it is nearly 9 now.

Bela is a village about 30kms away from Rapar. It is believed to have been very close to the sea once upon a time. The land eventually rose above sea level. Bela used to be a flourishing village for blockprint. That is also why we are here today.

“Have we reached?”

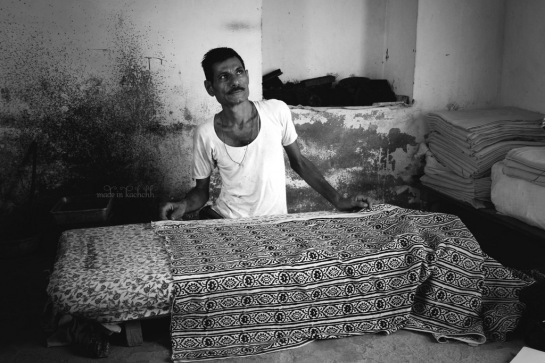

We enter the front room of a house, with a high ceiling. The fan is running at full speed with an unusual hum. The only other noise is the rhythmic thumping of wooden blocks against the thick cotton canvas cloth. There are two low wooden tables on either side of the room. Behind one of them sits Mansukh, with his old tiny blocks and the ubiquitous yellow canvas.

Mansukh is a Hindu Khatri.He is also the last blockprinter left in Bela.

Bela is an old town, maybe 300 years old, once ruled by Rao of Kachchh. The town today has about 200 families living there. They mostly do farming. Some of them have kept shops. The market space is closed during most of the time that we are in the village.

“They are sleeping. Shop will open when sleep leaves town”, says Mansukh.

He prints designs for bags, given to him on order by some businessmen(shops) in Bhuj. He has been printing the same thing ever since he learnt the craft and started off on his own. He also prints designs for cushion covers, the patterns of which are decided by the businessmen.

Mansukh works alone. He prints and dyes by himself. He still uses the same blocks from his grandfather’s times. No new blocks have been made since two generations. The blocks are really tiny compared to the ones I have seen in Ajrakhpur or Dhamadka.

Since they are half the size as compared to the new ones used by blockprinters today, Mansukh takes twice the time to print a unit metre of cloth.

Once he finishes an order, he travels to Bhuj with it. At the store he is made to check and count every metre of cloth in front of the businessmen who makes sure his calculations are correct. He receives Rs15 per bag!

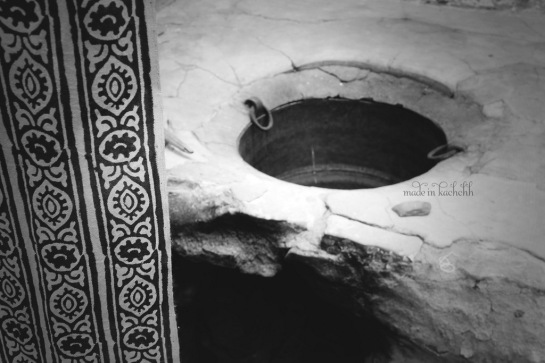

The front room leads into the courtyard of their house. It is here that the dyeing is done. I notice that the vessel used for dyeing is of old style with a narrow bottom, one that I had seen the previous day in an antique collectors shop. When was the last time he used it?

Drinking water is an issue in the town. A tanker fills the private tanks of people once every two days. For dyeing purposes, they had a canal earlier whose water was very kaadak(hard/salty), that dried up. So now he has to collect water from a bore well, a little further away.

“In Ajrakhpur, we are so lucky!” says Rauf. “We use sooo much water, sweet water!”

Beyond the courtyard lies the family home. The house was completely reconstructed after the earthquake, using the old wood and stone. It is charming even today. He has 3 children. The oldest one is working in Bhuj while the younger daughter and son stay with their parents in Bela.

None of his children want to follow their father’s footsteps.

Mansukh learnt the craft from his brother. His father died 40 years ago.

“How old are you now Mansukhbhai?” I ask him.

“I must be 50.”

His brother now keeps a sweet shop.

After the India Pakistan separation, the people started leaving the village of Bela for newer prospects in larger towns. They moved to Ahmedabad and even Mumbai. The town hence lost its visitors and slowly the only remaining people settled down to having petty groceries, milk and sweet shops besides agriculture. There used to be atleast 60 blockprinters in Bela. They have all closed.

“Why did you not leave?” I ask.

“I do not know anything else. This is what I do.”

“Yes, he had stopped in-between for a while, but he got back”, says his daughter.

She seems like a very clever child. His son is shy and has lost complete hope in his father’s work. He does not believe it is a ‘valuable’ thing to do. He is the youngest kid, probably 12 years old. Cannot blame him. We discuss about how a ‘blockprinting man’ will not find a wife now in Bela. It may be best for his son not to take over.

Mansukh shows us all the traditional blocks and some scrap pieces of old blockprinted fabric that he has. We speak about designs and take photographs. He even shows us a jacket that he had designed, but that was a while ago.

They offer us lunch. Delicious potato sag with tiny tiny pooris (just like his blocks), and sevaiyya (sweet) and chaas (buttermilk).

Mansukh is a man of few words. I cannot say if his silence is from wisdom or from lack of exposure. He is very isolated from the rest of the blockprint community of kachchh. He has a kind of naive curiosity about Ajrakhpur after lunch, “What do you make there?” he asks Rauf. Is it a question coming from a man stuck in the past?

“Come to Ajrakhpur and see. Sarees, dresses, stoles, bedspreads, you name it and we make it there!” says Rauf. Mansukh smiles, do I see a hint of hope?

We speak a lot to Mansukh’s son, Rauf tells him about how successful his business is in Ajrakhpur.

No reaction.

How blockprinting is done in several different ways and products.

No reaction.

How he gets to travel a lot.

No reaction.

How many foreigners visit his house everyday.

“Oh really!?”, comes the response. We show him pictures of Rauf’s workshop on madeinkachchh blog.

We hope they will visit Ajrakhpur.

When we are about to leave and start our byes, Mansukh says, “We had many more blocks. Traditional ones. But my brother and I had no use for them. We packed them up in a sack and dropped them into the river.”

Oh.

*********

Together with the Printers and Dyers of Kachchh

– The Blockprint Collective – an exhibition coming soon in December 2013 at Khamir

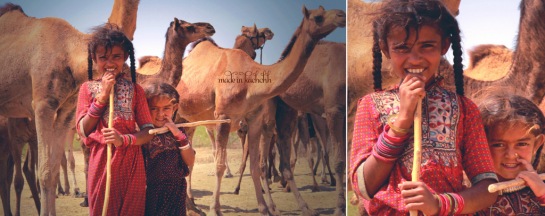

Ahmed-bhai, his two girls and their forty camels

It is the sunny season in Kachchh and the air is dry as ever. In the middle of the dryland somewhere in Western Kachchh, there lies a big pond where camels, we are told, stop for their mid-day drink. It is here that we wait for Ahmed-bhai to arrive with his herd of camels, and to my amusement, his two little girls!

Ahmed-bhai is a “maldhari”, a herder who breeds and looks after camels. A nomadic lifestyle keeps him and his family constantly on the move both within and outside of Kachchh. His family belongs to the Jat community whose forefathers are believed to have fled from Haleb in Baluchistan about 500 years ago. Following a feud with the King, the Jats sold all their other animals and replaced them with camels to prepare for their long journey traversing Sindh to eventually settle in Kachchh.

Mainland Kachchh has always lacked fertile soil. Just down south of the Great Rann of Kachchh, lies however Asia’s largest grasslands called the Banni. This led to a dependence on pastoralism, with camel breeders, sheep and goat herders, cow and buffalo breeders inhabiting the region for over five centuries.

A little while later, the camels arrive and move slowly towards the water edge. Within a couple of minutes we are surrounded by 40 thirsty camels. As if by ritual, the camels are milked and fresh camel milk is offered to us. “Start with a little if it is your first time.” they say to me. I slowly take a sip, I have never tasted such salty milk before! They call me to the pond and offer clear water collected from inbetween a few rocks, “Drink! Aren’t you thirsty?”

I take a large sip again.

To be a nomadic pastoralist is to lead a life of discipline guided by the principles of nature and animals. Pastoralists have always lived in complete harmony with their surroundings. They had formed unique bonds with the other communities from the region. Eiluned Edwards in her article about the symbiotic relation between pastoralists and other communities writes that farmers in Kachchh would welcome migrating herders and their animals into their farm land after a monsoon harvest had been made. The animals would graze on the stubble, effectively clearing the land for the next season’s sowing while their urine and manure replenished the land, acting as a natural fertilizer. In return the nomads would be given grains for their service. In addition, the farmers would get milk and ghee (clarified butter) from the nomads.

The nomads had a similar relationship with the Khatris (one who works with colour on textiles) in the region. The khatris made colourful clothes for the nomads, and were paid in milk and ghee. Sometimes, the extensive knowledge of the khatris of local herbs and plants came useful in the case of an animal from the herd that needed medical attention.

During the Green revolution, a lot of this changed. Extensive agricultural practices introduced year-round cultivation, fertilizers and eventual loss of grazing land. These changes tragically affected the nomadic pastoralists.

This afternoon however, unaware of the struggles with their semi-nomadic lifestyle, I sit watching in admiration. The young daughters Noorbhanu (5) and Hanifa (10) now have a fan. Hanifa displays such confidence with the animals, running behind the stray ones to bring them back to the pack. Her little sister Noorbhanu is always 2 steps behind her, strong and quick in their movements, I can see that they have already mastered their father’s work. When our eyes meet, I see the shyness and the curiosity of little girls.

“Do they come everyday?” I ask their father. “Oh yes! They love their camels!” he says.

Although their mother had not come along at that time, I later found out that she plays a key role in their lifestyle. She builds their home, she takes care of young camels when they are born and collects grasses to feed them. She prepares food for the family, typically consisting of camel milk, rotlo (wheat or millet bread) and tea.

Although their mother had not come along at that time, I later found out that she plays a key role in their lifestyle. She builds their home, she takes care of young camels when they are born and collects grasses to feed them. She prepares food for the family, typically consisting of camel milk, rotlo (wheat or millet bread) and tea.

Constant travel means their houses should be easy to construct with few and inexpensive building materials. Their special houses, put up entirely by the women in the family is known as the Pakka, made of kal (reed grass), jute ropes and wood. Between house work, the women also embroider clothes, quilts and if unmarried, their wedding clothes.

The camels have fed and drunk. They have been milked. They will now be sheared for their wool. Soon all the attention shifts to two maldharis, friends of Ahmed-bhai, who with their scissors select a camel with a good tuff of hair on him and begin to shear.

Ahmedbhai collects the hair and puts them in the make-shift cloth bag. Noorbhanu carefully picks up a tiny handful of camel hair from the ground that her father had forgotten. She hands it over to him. “She is very careful, my daughter!” he laughs.

Traditionally camel wool is used to make cheko; bags that are used to cover the udders of the female camels to prevent the young ones from suckling. Today they are giving the wool to Sahjeevan, who in association with Khamir are finding new markets for camel wool to increase income and encourage camel breeders.

Camels are sheared once a year. just before the onset of summer. This work is done entirely by hand. Some maldharis often shear their camels in wonderful patterns, as a result decorating their animals. It is possible to collect 1kg of wool from each animal every year.

Once the shearing is done, Hanifa, the older daughter goes away alone with the entire herd, taking the sole responsibility to direct them to their home. Meanwhile Ahmed-bhai sits down with the team from Sahjeevan to discuss matters. We find a small narrow path inbetween a few bushes where the ground is shaded and cool. We have all run out of drinking water, but no fear, the pond is closeby.

We talk for nearly an hour before Noorbhanu starts getting impatient. She nudges at her father and whispers in his ear. Her father smiles and continues talking. Two minutes later she says, “Enough of chatting papa. How much talking can one do! Let us get to work!”

She is applauded by all of us. Wah Wah.

———————————————————————————————————————

The visit to the pond this afternoon was a part of meeting and understanding the lives of the nomadic herders, for the project – The Biocultural Protocol Of Camel Breeders Of Kachchh.

Their life and spirit is fearless, this is how they have always been.

Here are more photos from this day,

———————————————————————————————————————

I could not meet Noorbhanu’s mother, however here is an album of the women from the Jat Community, thanks to Sahjeevan.

The Last Goodbye

Malakaka leaves behind a question for us ponder. Did we do enough? More importantly, did we do right?

—————————————————————————————————————

Wadha Mala Khamisa, or Malakaka as we all know him, passed away on 12th June, 2013. Most of us, the craft lovers, have either worked with him or met him at some point. We all feel a deep sense of loss at his death. His is a story about lost opportunities; it is perhaps the story of the majority of our gifted and talented artisans.

He was one of the first from his community to have stepped into the world outside his village and Kachchh. I look at his passport – made many many years ago, when he was a young man with long hair and bright eyes. Born into a community that was essentially free and nomadic, he had a fierce independence and pride about him. His community was no longer nomadic though they continued to exist on the edge. They lived in binaries – being in the middle of the village but out of it, being Hindu but considered Muslim, being poor but extremely rich in craft skills (the only type practised in India), being uneducated but highly intelligent, receiving much but retaining nothing.

He was one of the first from his community to have stepped into the world outside his village and Kachchh. I look at his passport – made many many years ago, when he was a young man with long hair and bright eyes. Born into a community that was essentially free and nomadic, he had a fierce independence and pride about him. His community was no longer nomadic though they continued to exist on the edge. They lived in binaries – being in the middle of the village but out of it, being Hindu but considered Muslim, being poor but extremely rich in craft skills (the only type practised in India), being uneducated but highly intelligent, receiving much but retaining nothing.

Malakaka lived and breathed his craft. He despaired when his children did not pursue it as seriously as he did. He travelled to cities for exhibitions. It had made him confident and open to new ideas. He was the first to support new initiatives. He was the most reasonable when it came to sticky issues but never compromised on price or quality. Everyone who came to Kutch searching for crafts ended up meeting him. Even the people in the Government bodies of handicrafts all knew him.

Despite a life that feels quite full, he remained a worried, unhappy man. His worries only increased with time. Like many members of his community, he had a long tryst with illness and doctors. One assumes a major part of what he earned went towards medical expenses. Life became an unending cycle of work-money-crisis-debt-work. He was heartbroken by the waywardness of his children and gradually began losing hope. The last time he came to our office, three days before his death, he had cried, saying he was tired of life.

Despite a life that feels quite full, he remained a worried, unhappy man. His worries only increased with time. Like many members of his community, he had a long tryst with illness and doctors. One assumes a major part of what he earned went towards medical expenses. Life became an unending cycle of work-money-crisis-debt-work. He was heartbroken by the waywardness of his children and gradually began losing hope. The last time he came to our office, three days before his death, he had cried, saying he was tired of life.

Long back when we had visited him with a group of foreigners who couldn’t stop praising his skills, he turned to me and said, “We have the talent, but not the luck. Our karma holds us back.” It was as if he knew that no matter what, his community would take a long time to overcome the burden of history.

Long back when we had visited him with a group of foreigners who couldn’t stop praising his skills, he turned to me and said, “We have the talent, but not the luck. Our karma holds us back.” It was as if he knew that no matter what, his community would take a long time to overcome the burden of history.

Malakaka leaves behind a question for us ponder. Did we do enough? More importantly, did we do right? Speaking for ourselves, we were unable to strike the balance between welfare, charity and enablement of the community. This conflicting approach must have confused even Malakaka. In the end, it was easier for them to fall back on the few things that were certain – the seasonal tourists, advances against orders, and the occasional charity support from organisations and individuals. We were unable to create the possibilities for a different future during his time.

As we said our last good bye to Malakaka that afternoon, he looked like a defeated man who had left the world worrying for his family. His body was being taken for burial though technically the Wadhas are Hindus. Twelve days later, there would be a feast for the community in keeping with tradition.

As we said our last good bye to Malakaka that afternoon, he looked like a defeated man who had left the world worrying for his family. His body was being taken for burial though technically the Wadhas are Hindus. Twelve days later, there would be a feast for the community in keeping with tradition.

By Meera Goradia, Khamir

Guest writer on MadeInKachchh

To know more about Malakaka read our previous post – Meet Malakaka

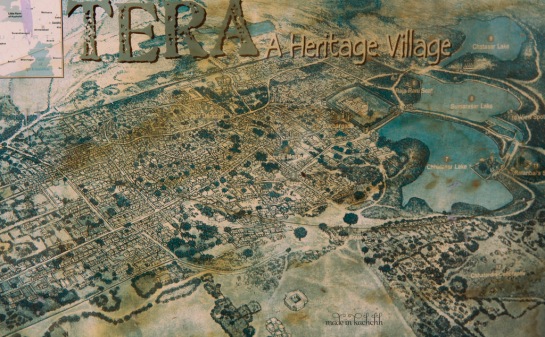

The Three Lakes of Tera

Nearly four centuries ago, a tiny village nestled in the Naliya grassland region of Kutch was sold for tera hazaar (thirteen thousand) koris (an ancient currency of Kachchh). It was an important port during that time and along with the other ports like Mandvi and Mundra, it contributed to much of the maritime trade between India and the Middle East, Africa and even the West. It was home to rich Hindu, Jain and Muslim merchants, who patronized the construction of beautiful havelis and marketplaces, temples and stepwells, tombs and mosques that adorn the streets.

This little village came to be known as Tera which means thirteen in Hindi.

Today, a walk through Tera reminds you of a once flourishing medieval town, retaining much of its symbolic power and grandeur in its architecture. The streets are straight and narrow, with an imposing fort wall dressed in stone known as the ‘Alampanah’.

If you happen to catch the chatting villagers during their afternoon tea time, they will proudly tell you what is perhaps the most unique feature of their village. The manmade lakes. To the North-East of the village, along its periphery lies this fascinating example of traditional water management systems. They are called the Chhatasar, Sumarasar and Chatasar.

Rainwater collected from the hills about 15-20kms away is brought to the village through a small canal. It flows first into the Chhatasar whose banks are sealed against erosion and the bed against percolation. The water from this lake gets filtered through a wier on the opposite end and flows into the second lake, the Sumarasar. When this gets filled up, it automatically flows into the third, Chatasar and eventually into the river Tera. This interlinking and sequential filtering of rain-water is remarkable.

The use of the three lakes was segregated into bathing and washing clothes, for animals, for drinking and other needs respectively.

Imagine the engineering skills of these people back then!

Fearless

These two girls had accompanied their camel-breeder daddy to work yesterday. It seems they come everyday, with their herd of 30-40 camels to graze them in the thorn forests.

These two girls had accompanied their camel-breeder daddy to work yesterday. It seems they come everyday, with their herd of 30-40 camels to graze them in the thorn forests.

When asked why, their dad said “oh they love the camels!”, their grandfather butt in to say “because they are the boss!”

After a while the older girl (10years) took off alone with the herd to take them feeding and then back home which was atleast an hour’s walk from where we met them, while the dad and the younger one (6years) sat down with us to talk.

I was amazed. This little ten year old was going off by herself with the herd.

Truely their education is very different from ours.

Fearless.

The challenge of eating ‘less’ but ‘better’

A visit to a village of weavers, this sunny sunday morning, made me think a lot and I want to share this experience with you. Bhujodi, a small village about ten kilometers east of Bhuj is inhabited by several craftsmen who specialize in hand-loom weaving. Besides the fact that artisans welcomed us to their homes as if we were family, they shared their knowledge with passion and without a second thought about selling anything to us.

First we meet Narayan-bhai and his son. They specialize in the manufacture of woollen carpets. Today it is a bit special, they are preparing for Diwali, the Indian New Year, so are coating the walls of their home with a mixture of mud, lime and cow-dung.

First we meet Narayan-bhai and his son. They specialize in the manufacture of woollen carpets. Today it is a bit special, they are preparing for Diwali, the Indian New Year, so are coating the walls of their home with a mixture of mud, lime and cow-dung.

However seeing our excitement to watch the looms work, they settle down at their looms and start weaving a carpet. Although I’ve seen weaving work before, I am fascinated! Beyond the technical moves that are impressive, the complexity and beauty of the machine leaves me speechless. All these lines, these regular movements, these colors … create an atmosphere that is truly mesmerizing!

They have 2 looms, fully manual. The one that Naryanbhai uses

and the other handled by his son:

and the other handled by his son:

My wife and I sit there for a long time just watching them work. Most of their production is for a client from Finland! They take about 1 day to make 1 carpet.

My wife and I sit there for a long time just watching them work. Most of their production is for a client from Finland! They take about 1 day to make 1 carpet.

They are proud to show that they have designed a carpet with three different types of wool: camel, black sheep and white sheep.

They are proud to show that they have designed a carpet with three different types of wool: camel, black sheep and white sheep.

They say they love the creative side of their craft, but do not have enough time to truly experiment since they need to produce carpets for the Finnish which are large orders and are always the same : gray and white…”european tastes!” they say.

They say they love the creative side of their craft, but do not have enough time to truly experiment since they need to produce carpets for the Finnish which are large orders and are always the same : gray and white…”european tastes!” they say.

And then there is Purushothambhai. If you can read the name correctly the first time you win a silk shawl 🙂 We had not even planned to visit his home, he catches us on the streets and says “come and see, I have something to show you.”

He begins by showing us a series of very finely woven shawls with a mixture of silk and cotton, then take us to his loom. It is much narrower than Naryanbhai because it is used to make scarves and shawls but it is equally impressive.

He begins by showing us a series of very finely woven shawls with a mixture of silk and cotton, then take us to his loom. It is much narrower than Naryanbhai because it is used to make scarves and shawls but it is equally impressive.

The thread is much thinner, and the weaving takes longer. Depending on the type of pattern, a piece can take up to 1 month. The method for doing this kind of pattern is inexplicable in writing, it has been a good half an hour to figure out how he is doing it! Purushothambhai is first and foremost an artist, he creates his own designs, his own forms … He sells his works everywhere in India, at exhibitions and events related to crafts.

The thread is much thinner, and the weaving takes longer. Depending on the type of pattern, a piece can take up to 1 month. The method for doing this kind of pattern is inexplicable in writing, it has been a good half an hour to figure out how he is doing it! Purushothambhai is first and foremost an artist, he creates his own designs, his own forms … He sells his works everywhere in India, at exhibitions and events related to crafts.

He tells us this moving story of how he once set off to create his “best” piece, he had already given three months of hardwork into it and while it was still on the loom and nearly complete, an insect ate into it. This piece hence will never get sold. But will remain with him to tell his story.

He tells us this moving story of how he once set off to create his “best” piece, he had already given three months of hardwork into it and while it was still on the loom and nearly complete, an insect ate into it. This piece hence will never get sold. But will remain with him to tell his story.

To be able to feel the connection between knowledge and the product is really a unique experience, it gives a new perspective on the value of things.

To be able to feel the connection between knowledge and the product is really a unique experience, it gives a new perspective on the value of things.

“The industrial era” helped us make a bunch of objects accessible in large numbers and at a price much more affordable than products that are “handmade”. This is what allows us to not have to save for two months to buy a pair of trousers, that I personally find quite handy … However, this “progress” has totally engulfed our concept of the “value” of things.

There is little or no information on the conditions under which the products we use are made, by whom, with what, with what impact on the environment and on society more generally. Take the time to take this step to “understand” a product, to look at it differently and go back again to the challenge of eating “less” but “better”.

Ghadai : by the potters of Kutch

“Ghadai” is a pottery exhibition conceptualized by KHAMIR, to showcase the handicraft of the Kumbhars, potters of Kutch. The exhibition will trace the history of the Kutch potters, as well as present exceptional pottery pieces created especially for the project. The word “Ghadai” refers to the name of the unique and highly skilled technique used by traditional potters to create large objects of pottery.

A new place, a new adventure

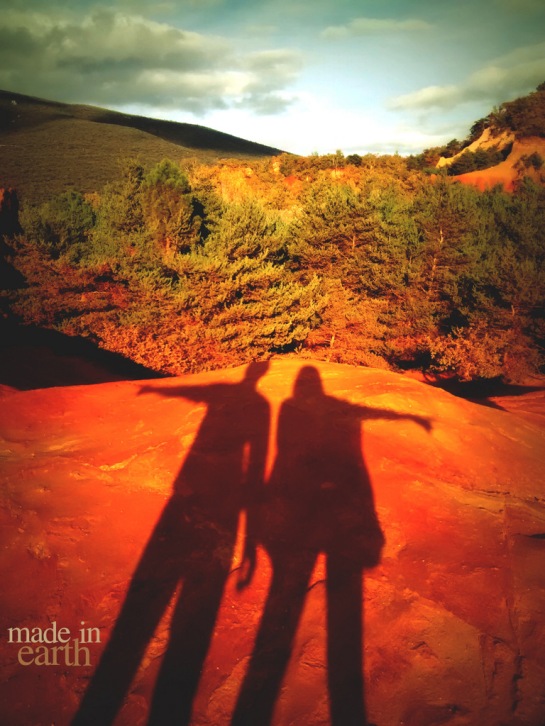

Big hugs from all of us for the love you sent us for Made in Kachchh over the last two years. We have now moved from the creative salt lands of North Western India to the great green rice fields and sugarcane stretches of the South. Our passion as architects and storytellers, has led to the birth of our new blog, ‘Made In Earth‘ where we promise to continue sharing and spreading stories about the places, people and projects we love!

We are passionate about building with earth, we love creating with it. Our journey in Kachchh has strengthened our beliefs in creating by hand; creating with what is around us. At MadeInEarth, we believe in the very same; “Building with what lies beneath your feet”. Made In Earth is where we share experiences and stories about our projects and the ones of those who inspire us.

Across countries and across generations, people are finding new alternatives to live a little better, to live a little closer to the environment. If it gives us the desire, the appetite and the curiosity to learn, to push boundaries and to create, we promise to share it with you and we hope these stories will do the same to you!

http://madeinearth.in/ Or you can follow us on facebook here : http://www.facebook.com/madeinearthindia

Happy Holidays everybody!

Enroute to Nakhatrana

Little Miss Sunshine

Stamped in God’s Mysterious Company

“Breath in,” Dr. lsmail Khatri pushed a yellow scarf in front of my nose in Ajrakhpur, a village of families dedicated to block-printing in Kutch, a semi-arid region of Northwest India.

It smelled like my lunch.

“Turmeric and Pomegranate skins for yellow,” Dr. Ismail explained. The smell is the way buyers ensure that the dye used is not synthetic.

Dr. Ismail was born into a centuries-old tradition of Ajrakh, or block-printing. His ancestors were recruited to Kutch from a historic province of Pakistan, Sindh, at the king’s request for handmade textiles in the 16th century. Now, he and his sons Sufiyan and Juned run a natural-dye Ajrakh operation. Their family home is a sanctuary for seekers of handmade textiles in India.

Under the ceiling fan in Dr. Ismail’s office, I unfold and refold hundreds of meters of handprinted fabric, layering myself in enough colors to rival Joseph. I ask about the patterns draped over my shoulders and learn that the teardrop shapes aligned in dizzying symmetry signify khareks, or sweet dates. Following the Muslim tradition, Ajrakh designs are aniconic: they do not depict human or animal figures. Instead, they represent local botany, ceremonious fruits and interpretations of the night sky.

I unearth the deepest colored fabrics from the Khatri’s inventory and hold them against my face in front of a mirror. In some communities of Kutch, color intensity of Ajrakh textiles denotes age: younger women wear lighter shades and graduate to darker colors with age, depicting the depth of their wisdom. Traditionally, printed motifs in women’s dress shift with each life-cycle.

Women throughout Kutch don unique Ajrakh traditions as communal and individual identification codes. In the Khatri family, when women become married they wear haidharo prints, floral motifs in red and white on a yellow background. When their son marries, their dress shifts to the jimardi print whose floral depictions are more intricate and printed in dark blues and reds on an emerald background. Once widowed, women of the Khatri family adopt the ghaggro print, a floral motif

printed in dark reds and blues. Men traditionally wear red and indigo Ajrakh turbans and shoulder cloths that double as spice sacks or namaaz prayer mats.

I recognize the weight of distinctions that my choice of fabrics carry, but am overwhelmed by my mission to select the prettiest. I leave them folded on a chair when Sufiyan’s wife, Hamida, calls me into the kitchen. I watch her peel carrots and hold her toddler until he starts crying. She takes her child and hands me a carrot peeler. Together we cook Gajar Halwa, a sweet made from carrots, sugar and cream straight from the family’s buffalo herd. Gajar Halwa is a treat traditionally prepared for special guests, of which the Khatris have no shortage. Designers, students and textile enthusiasts stream into their home to touch, smell and purchase Ajrakh textiles.

…

Nine hundred and fifty kilometers south of Kutch, Dr. Ismail’s cousins, Ahmed Khatri and his son Sarfraz run Pracheen, a block-printing studio in Mumbai with a kindred buzz. Years ago, Ahmed learned natural dye recipes and techniques from Dr. Ismail, into which he has since infused mysterious secret recipes that seduce some of the world’s top designers and India’s most worshiped Bollywood heroes.

From the outside, the Pracheen workspace in Southeast Mumbai is unremarkable. The main door is hidden amongst hundreds of others that look just like it surrounded by mobs of peddlers, merchants and animals. Inside, three dark flights of stairs with no railing lead to a small office that opens into a grand studio of long tables set with meters of stretched handwoven silk or organic cotton. Barefooted men shuffle along the narrow tables as they thump wooden blocks onto white space in a steady beat.

I remove my shoes and let myself into the studio. I pause in reverence as I witness the thousands of hand-carved wooden blocks stacked on top of one another and organized by the motifs carved into them. They line the walls of the studio representing hours of labor at the hands of artisans. Ahmed’s family lives on the floor below the studio and his goats occupy the rooftop terrace. Ahmed and Sarfraz serve fresh coconut water to each visitor, a trademark of their customer service.

“Do you know a woman from America . . . her name is Donna Karan?” Sarfraz asked me as I sipped from a fresh coconut.

“Like . . . The DKNY?” I asked. “Last week she spent eight hours looking at our cloth.” He handed me a photograph of Donna Karan swaddled in Pracheen shawls.

The Khatri operations in Ajrakhpur and Mumbai are both thriving. The families share a deep reverence for Mohammed, vowing that faith fuels their commitment to craftsmanship and beauty. While sharp contemporary angles mask some traditional motifs on the printed fabric, underlying patterns can be recognized in Islamic art and architecture. The Khatris credit God for their inspiration, creativity and business acumen.

The name Khatri translates literally into one who fills with color. The cousins in Ajrakhpur and Mumbai have the same indigo-stained nail-beds, exposing their possession of the secrets that transform local nature into vivid textiles. Both families honor the environment through preservation of water and commitment to the use of natural colors such as indigo, madder and turmeric instead of synthetic dyes.

Dr. lsmail remembers rubbing pomegranate skin water onto fabric as a child. His family was one of the first in India to document experimentation with locally found materials as textile dyes. When I first visited him, he took me on a tour of his backyard and led me to a tree.

“The bark is used for orange color,” he said, plucking at its trunk.

He then led me to a bucket of murky stew made from “rusty things” (bicycle pieces and scraps of fences). It had been fermenting with sugar cane and chickpea flour to yield a black color, which is used to outline the intricate designs on Ajrakh fabric. I gagged when I leaned over the top to look inside.

The art of Ajrakh seems to be magic, but the process is precise and laborious. White cloth is stretched and pinned onto a table. Printers, men trained in the precise art of Ajrakh, dunk wooden blocks into pastes of mud, resists that shield the adherence of dye to fabric and mordants that react with natural chemicals to absorb certain dye colors. The pastes are made from common ingredients including tamarind seed, arabic gum, clay and millet flour.

The printers, men from nearby villages, hover the mud-painted blocks over cloth to ensure symmetrical application and pound them with heavy-forced whacks hundreds of times until the cloth is completely stamped with designs. Sawdust or buffalo dung is immediately sprinkled on the fabric to prevent the prints from smudging. It is sunbathed to dry and then dipped into fermented indigo, which is light green until it is oxidized into deep blue. After it dries in the sun again, it is washed and beaten, removing the mud pastes from the cloth. This process is performed several times until the cloth is transformed into a multicolored mural crowded with time-honored motifs.

Historically, Ajrakh was an important part of the economic web that sustained Kutch’s interdependent barter relationships among families. A family of weavers might trade hand-woven turbans and shawls to the Khatris for printing. The Khatri wives might embroider ornamentation onto the pieces before trading them back to the weavers for more goods. High-skilled artisans reserved their masterpieces for dowry collections and labored over unique ornamentations for wedding celebrations. Families created handcraft in synchronicity with community needs.

Today, the Khatris’ work is celebrated on international runways. Dr. lsmail, Sufiyan, Juned, Sarfraz and Ahmed work closely with designers from all over the world and study fashion magazines to broaden and enhance their tradition. Visiting designers can draft their own wooden blocks, but most choose from the Khatris’ traditional collections. Blocks are retired when the edges turn rough or become uneven. Dr. lsmail has blocks that are over 200 years old.

…

When I step into the Khatri sanctums, my heart beats faster. I touch everything from the frayed edges of unfinished samples to the cheeks of children playing with wooden blocks. I hold babies, pour chai and wander into kitchens. I feel cloth for rough edges, loose loops of thread and spots where the dyes didn’t soak in evenly.

When I was young, my mom was my personal shopper. She’d come home with multiple outfits and force them over my head as I stood passively with my arms up. She usually ended up returning all of her purchases, only to try again. I hated shopping. I still can’t figure out how to select the right blouse out the hundreds of starched variations, each with crunchy paper tags dangling at their sides. The gaudy colors and crisp fabrics that hang perfectly under the fluorescent overheads are supposed to go on my body? The idea of it feels too far away.

Shopping for Ajrakh is a loaded venture. My purchases are guided by human connections and histories that come alive in the fabric. I shell out too many rupees without regret because I know that the shawls I purchase are stamped with pride, tradition and God’s mysterious company.

————————————————————————————————-

This article contributed by a dear friend Shaina Shealy, originally appeared in the Hand Eye magazine more than a year ago. Shaina is a wonderful photographer and story-teller who loves (and lives) to cook and feed people! Here is a link to her mom and daughter food blog, handcrafted with love, Cross Counter Exchange

Thank you Shaina! And much love from Kachchh!

————————————————————————————————-

Visit Kachchh Ji Chhaap, an exhibition of 500 years of Batik and Blockprint at Khamir, Kachchh

![Final Invite CC [Converted]](https://madeinkachchh.files.wordpress.com/2015/01/1-invite_ghadai.jpg?w=545&h=365)